AI is STEW, it’s made of people!!!

Category Archives: Opinion

Nuthin’s for Free

Some learn that energy is conserved, and that energy can neither be created or destroyed. Put another way, what you put into something you get out, you get what you pay for, or nuthin’s for free.

Since the late 1990’s, Google’s search engine has refined its ability to produce references to answers as we chase about the things we might or do need.

In the older days, librarians and their libraries played the role of producing answers to questions, and assisting in our research. Then we would have been climbing narrow dusty steel stairs in poor lighting to a fifth or sixth floor stack, where books organized by Dewey could be pulled from the shelves, and their pages explored.

Hopefully portions of solutions could be derived from the readings, often by tenacity and chance, when we would carry the books back down to the main floor and pay a fee to stand in front of a Xerox machine, shifting facedown open books and grabbing facsimiles of the relevant pages.

The time and effort normally allocated to investigation and research, now deferred to Google, whose distributed computing model is extensive, and mostly delivered with equity, at least for those who have access to the Internet.

But nuthin’s for free, even Google. In exchange, we stomach the search algorithm’s perceptions of what might prompt our attention through admittedly what seems to be mostly benign and unobtrusive advertisements.

Scary is that only days earlier when looking for vintage Campagnolo derailleurs, like a big brother, Google somewhat with bias, dishes up an alluring series of available and related bike components to consider among a seemingly non related query.

But mostly, when subtle and smart, I nod thankfully for the time saved. After all, better advertisement than paying a subscription to search for solutions from any of the search engines available these days.

Enter artificial intelligence, computing algorithms that have been trained by the masses to produce even more relevant searches to solutions of our problems, identifying vendors for derailleurs in fewer clicks, better quality, more reliability, even creating accurate prose that might argue why newer technology would make for a happier ride in comparison to the rebuilt relics that are preferred.

Now inspired to drop some money on the new technology, deserving to the selected bike shop is that shop’s agreement to pay a fee to the search engine, a sort of finders fee. After all, nuthin’s for free.

Enjoy A.I.’s seemingly accurate and timesaving production of information that benefits your lifestyle of choice. Eventually you will have to make a choice if paying for the information is worth your effort, because inevitably the precision and accuracy will be offered at a cost.

Otherwise, you will have to go old-school and figure out the solution yourself through experimentation and possibly serendipity.

Cars and Guns

Back in the day there were cars, leaded gasoline, catalytic converters were just moving from experimental to full production nationwide, and there was noxious smog.

I spent the first twenty eight years of my life in Louisville, Ky, a geographic area which is fraught with a tendency to enclose hot humid air, the Ohio Valley, and cars were barely realized as a primary source of the smog laden air breathed by each a Looavullian’s lungs.

Burning coal for electricity was another misunderstood source. [1] Policies for emissions from coal plants could be more easily negotiated, as there were only a relative few to negotiate with, but for car owners, reaching a unified perspective was another story. In the United States, according to the Department of Energy, as way back as 2014 there were 800 cars per 1000 people, that is 0.8 per capita, topping all other countries in the world, and trending upwards. [2]

In the late 70’s a goal was to curb automotive emissions and thus constrain the smog that was leading to an increase of asthma in our children, and what was determined later, the deterioration of blood vessel walls in adults. It became apparent to some that the necessary regular maintenance of an automobile could not be de facto trusted to their owners, and thus a law was written, and Vehicle Emission Testing (VET) monitoring sites were established. [3]

Beyond maximizing the efficiency of the balance between consumption and emissions for the notoriously inefficient internal combustion engine, another concern was ensuring safe operation of the cars we drove. Put simply that tires, lights, windshield wipers, and brakes were up to snuff. In all some two dozen points on a car were checked – I specifically recall watching a mechanic attache a jig to aim headlamps most interesting.

Rest assured, after a run through of your car from a VET professional, typically a local small shop mechanic who fortuitously realized the financial and optimistically the healthful opportunities in leading a certified VET center, the safe operation of one’s vehicle was validated in a short twenty minute appointment.

My parents separated when I was becoming a teenager, their four children born in five years. Partly because of the hard times, my father struggled supporting us. Hand-me-down cars were typical in our home, my sister Anita shared her 1982 Ford EXP, a burnt orange car that kept Ma from taking the bus to one of three jobs, and the grocery. Said differently, there were zero excess dollars to spend on an annual VET inspection and likely repair bill, nevertheless she routinely complied with the law to verify emission levels and to certify the vehicle.

Fortunately, when that less-than-efficient car did sputter and fail, there were straightforward policy mechanisms to extend the length of the test period, citing hardship for example; I recently stumbled onto my letters requesting VET extensions annually, even after moving to Minneapolis to attend graduate school in physics.

The bottom line is that with honest responsibility demonstrated, it was fairly easy to get an extension and keep driving legally on public roads. There might have been a sticker that was attached to the license plate to announce certification broadly. Moreover, trucks used by licensed businesses were exempt from testing, suggesting thoughtful, even non-onerous latitudes were built into the policy.

The point to be made is that there was a law created because for-whatever-reasons we could not trust our neighbors to maintain the efficiency of their automobiles, and who seemed removed from the collective effects of car ownership, “oh shucks, what problem could my little old car have on noxious pollution and health the good people living in Louisville?” When multiplying 0.8 cars per capita by the metro population of 612,890 (using 2014 census data) for the integrated effect, plenty. [4]

This morning a news story captured my attention: last year, just short of 50,000 people were killed by guns in the United States, a horrible and large number. For perspective, these include homicide, murder, unintentional, and defensive use. For 2023, mass shootings and mass murders totaled 339 (as of June 19), from all of 2022 that sum is 682. [5]

For the dead 50,000, there are another four who were directly affected by the loss of their loved one, and another ten who were at least moved spiritually when attending the funeral services. That is, an estimated 750,000 were affected by gun violence in one year. Let’s call that estimate 1,000,000 annually, a horrible and large number.

A logic statement is that gun violence touches many and is a recurring problem in the United States, and for-whatever-reasons we can not trust our neighbors to maintain an efficiency at owning and using guns, and now must create laws to ensure (societal) function and safety.

Like the VET centers and the multi-point inspections, we propose Gun Ownership and Use (GOU) centers, where good people are certified for ownership and use, those ignorant to the goals of the program are enlightened, and gun ownership for bad people is squelched.

Who among us would comply with a gun certification process? Why of course gun owners – if you do not own a gun you need not jump that hurdle, but then again, you might elect to proactively be certified for ownership; for example there are numerous passport carriers who do not travel abroad.

To be clear, the proposal is that there would be regular checkup on gun owners analogous to the practice of monitoring emissions and safety of cars, because we can not trust people to manage themselves.

If you want to own a locker full of guns, fine, that is your right, and my right is that gun owners schedule an appointment at the GOU to make sure the metaphoric “tires, lights, windshield wipers, and brakes” are functioning properly. That is, when the rubber hits the road, you can see the realities of ownership, and stop transgressions personally, collectively, and possibly you might influence others to similarly good practices.

The basic ideas is that people would meet with a trained professional to verify their responsibilities associated with gun ownership. The GOU could be populated with trained bachelor degree-ed psychology majors to save costs so as to not constrain the already taxed psychologists who are working through an unprecedented mental health crisis in our nation, allowing for a more seamless growth of a new practice.

For the first decade of a gun ownership law, costs could be fully absorbed by State governments, funded through block grants by the Fed; devising the funding model and the program’s ROI is better left to law makers.

Certification levels could be decided on: own one hunting rifle, no problem, own three hunting rifles and two pistols, that’s okay, or twelve of both, or any quantity, go for it, after passing a “multi-point inspection,” a person’s certification for gun ownership might be reported on a drivers or hunting licenses.

In service military, police, fire, and ambulance personnel, pilots, even TSA-certified fliers could receive expedited gun ownership certification.

Suppose you are that retiring sheriff who has been collecting guns to sell as a supplement to your retirement years, you’d receive a stamp of approval to own some range of guns: 1-3, 3-10, 10-24, 25-100, 100+ for example. The point, ensure latitude in the law’s implementation.

It might prove that visiting the GOU annually is too frequent, similar to obtaining a boating license once per three years, or like a passport once a decade. The more times I see the dentist for checkups, the better my dental health is with implications for my overall health, but going once per month is superfluous. Again, let the people and law makers sort out and monitor the effective frequencies.

My parting shot: ensure reasoned gun ownership for hunting wild game and for protecting one’s life and personal property by ensuring operation and safety of guns for the masses through regular center-led evaluations and certifications.

Sun’s Set

Imagined Empathy

Sun’s earlier rise welcomed, winter’s hold loosening, turkeys perched in the surrounding oaks rustle; arm cocked, elbow high to trigger the dark rich flow of caffeine; the wooden deck pops loudly under steady weight, expansion natural when warming; across a deep frozen but narrow river, a crackle is noticed westerly, assumed to be morning foraging deer, meditations of early settlers bank-side easy, until a muted metallic snap pierces the cold dry air;

leafless and sagging tree branches span much of the snowy intersection, some 100 meters of undulation after a steep descent from where I now squat; two red laser dots reflect shakedly on the half open glass door behind; as aims are refined, gasses stir in my stomach, heart rhythms shaken, enemy is no longer an illusion;

surrender pointless, I contort and slither across the doors threshold into protection and collect my weapons of defense which include inconspicuousness; fortunately partner and three of four pets heeded wise calls for a southern exodus; for this hinterland homeland, a sustained unimagined attack is as real as the blue steel greed that caustically erodes long friendships, divides a fearful faltering nation, scraping away more than a half century of enlightenment.

Nature Prevails

As our river house sees nearly annual snow-melt floods, the lowland becoming long soaked in murky waters, and when retreated, a muddy mess. With warmed air, deep-rooted grasses and indigenous ferns sprout first, claiming the land and shunting the growth of non-native weeds that had previously encroached the area. Later, with mild winds, top-heavy box elders crash to the ground, roots rotted by the repeated floods, nature prevails.

Lady

The beautiful, so committed to beauty, you no exception.

Eyes unmatched, amber pockets bursting sparkles from within a green glow,

illuminated by the sun steeply setting over my shoulders.

A smile relentless, pearls set among a broad crimson suppleness.

Your face, geometric.

This is what all see first, many mesmerized, some eternally grateful.

Gold produced from bare metal

Science is sorcery to the simple minded, his locomotion preferably focused essential.

All her aim is on truth manufactured from experiment, impervious to life’s murder.

Too few suffer the difficulty of a sustained investigation, instead become saturated in the thoughtless grind.

A mistake of the educated is in their inability to empathize with the blinded.

Meandering Outdoors

A recreational plan is being developed by the Fargo Parks District for the quarter mile wide trench which will become a direct pressure relief valve for tens of thousands of welcoming homeowners in a proximity to the Red River of the North.

Cyclists, runners, and horseback riders will navigate unencumbered, a meandering and contoured multi-use trail spanning the bulk of the thirty mile channel, enjoying spectacular summertime sunsets and far reaching thunderstorms that only the horizons in the Dakota’s offer.

Skiing groomed cross country trails under the brilliantly sunny January skies will prove again the robust resilience of the upper-midwesterner. Labrador accompanied snowshoers will be trolloping in heaven. Snowmobiles whirring by in the main channel demonstrate the friendlier features of the new electric machines.

Spanning the Red are two young smart cities, Fargo and Moorhead, both software-enabled, recursive innovation a key theme. Young minds, young bodies require the outdoors and music. Bring on the F/M Area Diversion Project, please.

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fargo-Moorhead_Area_Diversion_Project

Meditating Squirrel

“Seems the ones that grow best are those the squirrels plant,” said the forestry guy offering proximal oak, dead standing and soon to be hewn.

The many oaks on the point are big and strong, spraying acorn biyearly, a sprouting white oak many years from participating, volunteers growing often at a disappointing rate, leaves diminutive and crowded.

What is their technique, depth, softened soil? Might the buried seed be cracked, enzyme triggered? Location genius?

Coded biological instruction: bury some fraction of the haul for tomorrow, that is for sometime beyond dozens of years, at a time when the individual squirrel is no more, only tribal progeny.

Meditate on that.

Without Beer

Without beer, what is music –

Live, outdoors, wind swept sunsets, thousands

Forever seeking, redirecting, the music pours as a thin veil

Memories triggered, driving to Colorado,

a CD becomes a friend, its pulsed beats, revisited lyrics,

Evaluated players impressing, smiles, cheers

Waves of opulence stir emotions,

Without beer, what is music?

Winter Blues

Game, games, gaming … this is life in the Hinterland.

Obfuscated Reality

His tribe, progress slow

The damp shaded forest, a shelter

Fired warmth limited, instead shivers managed under wooded bundles

They operate the moist darkness content that morning has come once more

Never forwarding beyond despair, never breeding knowledge.

An ordinary voice rings the horizon, catching latent attention

Fatigued, shivering, capacity for innovation challenged, eyes open with desire

Standing at the forest boundary, souls trusting submit

Alien possibility resonate with the cadence of the approaching machine

Hardened angst obfuscating reality, the loudest voice is heard.

Sequestered fears resolve into hope by the believers

A daily march begins toward fulfilled promise

Bias, righteousness typically necessary by each convert

While the displaced carry on numbly

Harshest is the reality that truth and equity are not goals.

Potential lost

Was it in a retreat, a grazed shot fired by a rightful hunter

Was it a poached attempt, an arrow

Was a parasite responsible, or other malady

His gait no more, sisters wander skittish without that watchful eye

Youth lost, hazard unknown, progress deferred until another time.

Matthew

Days before the announcements, where will he land, beating the crowd we stow basics for three days, adding ice to our freezers, a generator on backup.

Weathermen, civic leaders pronouncing danger begging heeded warnings, mandatory evacuations in reality subjective, considered by any whose probabilities exceed threshold.

Where he’s been, devastations, unbearably the downtrodden recanoider, striving forward after being stung by nature.

Where he’ll go is certain, to dissipation but when?

There is solidarity across disasters for those who have fought their own battles, while the inexperienced might empathize fractionally.

Let us pray.

Trotting Time

She runs, runs erect, runs direct, her cadence steady

Rhythm spawning contemplation, a mind focused

Past the blue spruce grove, alone, her dark two-tone drobe blending in ghost-like

There, in our presence, this unfamiliar runner trotting time away, step by step.

Native Sun

A product of environment, triggered intellect in response to thoughtful solutions, patient and aggressive, but waiting, operating under restraint imposed by the normalized, commitment to country preceded by his accumulated travels throughout his home state, cities dispersed rurally, most in advance of global connectivities, a back turned to naive hope, as a native sun’s capacities are lost, progress slowed.

Life or not

Self important and lonely, granddad weebles mask-fully around the coffee shop where I sit.

Anxiety expressed when a brother, thin and food conscious is diagnosed for a heart transplant.

Fear for a beauty whose nose pearcing went awry.

Remaining conservatively dormant for longevitys sake allows for Saturday morning coffee parties where nothing is said; sometimes instead over drinks.

Only children matter in suburbia.

Ground gaming

At two he sits in Daddy’s lap, pretzels, beer, third down replay, call reversal, then the game changing score, the youngster, bouncy yet robust-fully buoyant, landing back down on the leather couch up watches outrageous jubilance.

At six, balls are chased, kicked, catching learned, the sun blazen with vitamin D branding activity as necessary.

At fourteen, fighting biology and adolescence, he reigns approval from distant dad in showcasing atypical abilities in coordinated outdoor competitions.

At twenty five, college days behind yet tailgating emotions continue as resources are redirected, armchair quarterbacks abundant, triggers of those bouncy memories exponential.

At forty, managers steer their teams toward production utilizing that prevalence, purple and white colored cake sliced as celebratory reward.

Each game binary in its outcome, a winner, a looser, no ties allowed, a three sided die exacerbating the dichotomies, and stadiums crumble by the impassioned.

Politics: go red go blue!

Animal Behaviors

What dogs eat first,

soft, rich, and savory

like ice cream, easy

What dogs eat second,

hard, stale, crunchy

which requires work

Puppies are no different

Breathless

In their fear, the insecure thump their chests announcing security.

Common denominators suggest shared responsibility, but imbalance evidences prejudice.

In the need for support, development, and inspiration, negligence is insisted.

Breathless and dismantled, integrity and tenacity remain.

On North Dakota Coal

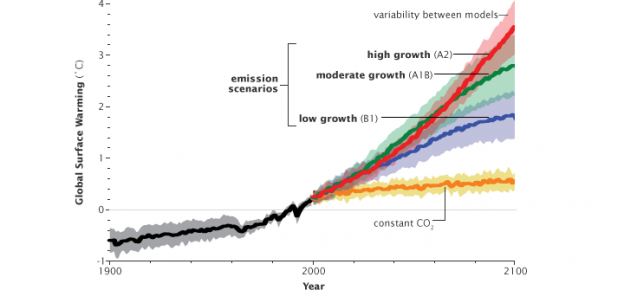

Climate change is a fact1, the inefficiently captured work of combusted fossil fuels among the most notable culprits.

Personal transportation, seemingly a right, has petroleum consumption at a sustained high2, with each mile driven adding carbon to an atmosphere3 that we breathe and that protects all of humanity from the destructive rays of our Sun.

Continued burning of fossils mined from the Earth without balance is unthinkable; the lake is not infinitely big, releasing your tired oil directly into the creek had to stop.

Getting to a point of balance on consumption (emissions) and need is daunting, and that effort will extend beyond any of our lifetimes, 100, 200 years forward.

Coal-fired electricity generation has become an easy blame4, with the individual’s automobiles tertiary, in part due to scale: a very large power plant versus my single automobile – a discarded watch battery ending up in a landfill certainly can’t be the problem, can it?

American’s inabilities with conceiving scale and utilizing mathematics renders hindered understandings of the reality of the situation.5 Instead we let the effects of a heated atmosphere creep up on us exponentially when only to discover an irreversible cascade that will gut biologies, and economies. Yet Mother Nature will survive, she does not require the foolhardy to propagate.

And you and I need transportation, we need electricity, we need heat, and appreciate air conditioning, but can we strike that balance with less emotional fear?

Coal in North Dakota is a vital part of the electricity generation picture that should continue as we develop reliable and efficient technologies as alternatives.

Coal in North Dakota is working hard to improve on the processes of efficient combustion and transmission of electricity, and there is no better demonstration in the Nation than at the Great River Energy Coal Creek Station at Falkirk, ND.

Since inception, Great River Energy has led by example in design, in efficiency, in cleanliness, in transmission, in reclamation, with worker excellence, safety, and stewardship.6

As mankind works together to avoid the irreversible, hold captive not the producers of electricity who respond to need and opportunity, challenge instead the consumers who remain ignorant to individual significance to the problem and the resourcefulness to conserve.

Insist on investments in technologies that harness renewable energies, in solar and wind, power storage, even sequestration: could incentivizing the creation of massive oak plantations7 contribute to that balance? And do we need government to force our hand?

Only as alternatives come into fruition will the debate be tempered, rendering tertiary the necessity of the burning of fossil fuels.

References:

- http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/GlobalWarming/page5.php

- http://www.advisorperspectives.com/dshort/updates/DOT-Miles-Driven.php

- http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/sources/transportation.html

- http://www.ucsusa.org/clean_energy/our-energy-choices/coal-and-other-fossil-fuels/how-coal-works.html#.VEk70YvF_p8

- http://changetheequation.org/press/new-survey-americans-say-%E2%80%9Cwe%E2%80%99re-not-good-math%E2%80%9D

- http://www.greatriverenergy.com/makingelectricity/coal/coalcreekstation.html

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2359746/

Shooting Star

Seas of desperation, despair, sagging decay

Seas of desperation, despair, sagging decay

Closer doorward some being entertained, smiles

Retina flash flash flash

Winners are silent

Killed 56 VC said the wheel chaired elder patriot

Smoke is thick on the reservation

George Thorogood playing earlier,

now even more Northern bound, and at night,

contributing to experimental evidence

to justify the truth.

Time to Die

Death as an industry, optimized to be self sustaining, innovation squelched to ensure profit, not life, too often shift workers lacking monastic attitudes of service to anyone but themselves.

Whose life matters but your own, and with age, that glint in the eye, that sparkle fades, eventually we give in to the invading army of bacteria, feeding on their host, as caterpillar eat all the forest, selfishly.

But in my seventy two years, I did this… I did that…, earned a few bonus years, came to appreciate my parents sacrifices for my life, but eventually its “time to die,” and my control of that day, that hour, that minute is limited—

One day we will time out before we die for man will invent anti-death, extend life for a time, and for a cost, feeding the industry of death.

A tendency to believe

Complicated by the obtuse most elect to trust their instincts

Those same human behaviors that catalyze fear and insanities

To imagine a time when action at a distance was deemed sorcery

Invisible forces are now understood, yet we refuse to indulge reality

Mother Earth could care less about the human species

She could easily shake us fleas from her back in one vigorous episode

As a host approaches it’s exponential limits, as a cancer spreads without remission, our obesities will consume us beyond repair

Ruled by greed that ridicules the impoverished, that hoards resources beyond any one person could eliminate, or could their designee, or corporate partners, or tribe of confidants, that feeds insecurities into righteous power

My concept of fair share is not the percentage rules we impose as an averaging technique used well before globalizations influence, instead a more rationale use base that can be documented, calculated, and modeled in any techno centric data driven society

Centralized power results in self effacing decisions that run its course, as the Mayans before, as the dinosaur lost access to the food needed to survive, we die.

Mother Earth could care less about us, we perish, this rock will remain.

The end is near | whatever

On Human Nature and Spirituality

A condition of being human is to be subject to the limits of the body. The realization of the infinite expanse of the physical presents then a condition of inferiority, a nothingness. Cast then a extra-human state called spirituality, where we align with that infinity who is by definition inclusive. In the focused attempts to be extra-human we manage a dialog that allows endorphins to flow in our brain machine giving the impression of rightness, or comfort in some, challenge in others. Like the design when standing on a high cliff, my being flutters when approaching the danger of falling, an attempt to maintain life, our brain machine triggers a rightness of spirituality, where that inclusive All becomes infinitely lovable, or at least when our pilgrimages for truth allow.

Water Runs North

Challenged by flood-related road closures, a recent drive forced me onto gravel farm roads some seven miles from the main stem of the Red River. It was clear that water had accumulated in their drain ditches but had moved through the system. Evident was a suitable depth held for a time with the dark top soil smoothed and flattened into a ceramic like surface. Fields were mostly clear of any standing water as were the ditches, at least those distanced to any tributaries.

Why flash the Red, the Sheyenne, the Maple? Why not hold the water?

Why gouge the table-top landscape with man-made ditches but not use these as storage capacity?

The quick drainage of the 5000 square miles of agricultural land is suspect, as are the addition of non-porous surfaces associated with urban sprawl, and the levees we build to hold back the relentless Red.

What of the prairie potholes that were drained, and not replaced, taking that many more sponges out of the equation of absorption, retention, and slow peculation?

Has the systemically warmer temperatures realized over the past decades been included by the modellers?

What are the real costs of denying that Mother Earth can get along just fine without us?

A design for a timed release of water will allow for us to coexist with nature.

Snow Melt

The mechanism of fear transfers reason into irrational action which catalyze uncertainty, reversing progress, a goal of the fear mongers who enjoy attention to their theories.

Water, Fire, and Air

Sunlight, music, dogs, warm feet, patience, and wind, the essentials, as is being grateful.

Venus over Walker

A disintegrating force caramelized one building and adjoining lot, stochastic and abrupt, shaking the dust off, announcing “too close for comfort” while one breaths no more, explosive energy, I explain to

another about 1974, snap a few pics, board, wave, travel, stop, with a need for peanut m&ms, lost serendipity is when you interact by rare chance, or that intuition prompts, but take no action, eventually arriving in Walker, where the winds blow, country music pounds festively, nearby a waxing moon is accompanied by a planet Venus.

Sisters

Four cottonwoods grew sided to each, tall in stature, sloped banks, over a bear cage now submerged, the resident three draw essence from a river Red which pushes wide, readying for a morning crest, and anticipating the formation of ice castles at their feet as a slow descent begins. Under open and cold skies Sister Four is no more.

Water Flows

Decisions which influence river dwellers are located at the intersection of urban and rural living, are made in thoughtful realistic and practical ways where no others are asked to compromise their beliefs of safety and longevity, costs internalized, and the impact of their contributions to the sustainability of the region realized as significant.